For many, the "secret war" on Laos remains exactly that - a secret. If you have never visited this country, there's a fair chance you might be unfamiliar with this concealed part of history, a shadowed chapter obscured by the infamous Vietnam War, or as it's called in Vietnam, the American War. Intriguingly, these two conflicts are inextricably intertwined, despite Laos's official declaration of neutrality in the Vietnam War.

Laos found itself embroiled in internal strife, searching for a new government structure following France's departure from Indochina. Unluckily for them, part of their land was seized by North Vietnamese forces, making it a key part of the Ho Chi Minh Trail—a corridor in the tropical jungle used by the North Vietnamese to deliver supplies to their troops fighting in the south.

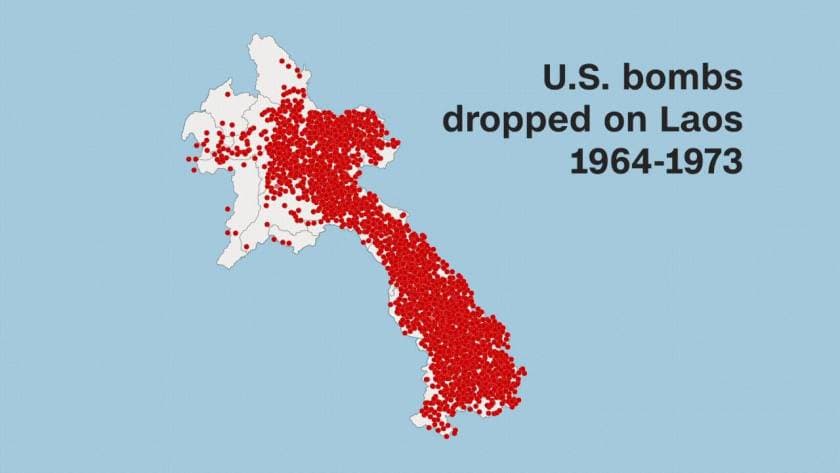

Between 1964 and 1973, an estimated 2.5 million tonnes of ordnance were dropped over Laos by the U.S. during 580,000 bombing missions[1]. The vast majority of these devices were represented by the so-called cluster bombs. These ordnances, typically dropped from airplanes or helicopters, contain a number of submunitions called bomblets. When the main device, or cluster, activates, these bomblets disperse over a wide area through various mechanisms.

Inside of a cluster bomb full of bomblets, on display at the COPE museum in Luang Prabang

The horror of this secret war doesn't end there.

What's particularly distressing about the use of these cluster bombs is not just the immediate, indiscriminate slaughter they caused. Around 30% of these lethal devices failed to detonate, leaving behind a deadly legacy that continues to plague the Laotian people. Of the 260 million cluster bombs dropped over Laos by the USA, approximately 80 million remain unexploded. Known technically as Unexploded Ordnance or simply UXO, these dormant killers continue to endanger and pollute vast areas of Laos, especially in the eastern part of the country.

The appalling reality is that the remnants of this war continue to linger, unacknowledged by many, yet devastating in their impact. The story of the secret war on Laos is a chilling testament to the long-lasting scars wars can inflict on a nation, hidden from the world's eyes, but never from the people who must live with the consequences.

Laos' journey to independence and the Lao civil war

Laos was a French protectorate from 1839 to 1949 and fell under Japanese occupation during World War II. As the Japanese withdrew, Laos became entangled in the regional struggle for independence, as part of the broader French Indochina War, or First Indochina War, which swept across all Indochina countries. This conflict officially came to an end in 1954 with the Geneva Convention. Within Laos, political instability escalated into a civil war, with key international parties like Vietnam, France, and the U.S. significantly influencing the course of events.

Internally, the contest for control in Laos was principally fought among three factions: the neutralists, led by Prince Souvanna Phouma; the pro-Western royalists, led by Prince Boun Oum of Champassak; and the communists, known as Pathet Lao. The latter originated as "Lao Issara," an anti-French nationalist movement founded on 12 October 1945. The name "Pathet Lao" was adopted in 1950 by Laotian forces that aligned with the Viet Minh's rebellion against French colonial rule in Indochina during the First Indochina War.

On 22 October 1953, the Franco–Lao Treaty of Amity and Association transferred the remaining French powers to the Royal Lao Government, leaving military control as an exception and marking Laos as an independent member of the French Union. In the subsequent years, the three aforementioned factions battled to gain control of the country.

1954 brought a turning point when the communist Việt Minh army, led by Ho Chi Minh, defeated the French, forcing them to surrender on May 7, 1954. The next day, the Geneva Conference began, with one of the primary agenda items being to resolve lingering issues from the First Indochina War. The discussions on Indochina culminated in the Geneva Accords, a series of treaties that divided Vietnam into North and South and called for the French withdrawal from their Southeast Asian territories, including Laos. This effectively formalised Laos's full independence. It's worth noting that the United States did not sign this agreement, fearing that the loss of French influence might lead to a communist takeover in Southeast Asia[2].

Following these accords, Prince Souvanna Phouma was appointed the new head of government. Throughout his reign, he attempted, unsuccessfully, to foster national unity.

Following the signing of the accords, the Pathet Lao solidified its control over two northern provinces in Laos, functioning almost as an extension of the North Vietnamese. With the backing of the Viet Minh, they began to venture into central Laos, sparking a renewed civil war as the they rapidly seized large portions of the country. A brief respite came in 1957 when a coalition was formed between the monarchists and the communists, temporarily halting the conflict.

However, in 1959, North Vietnamese forces invaded Laos with the specific aim of establishing the Ho Chi Minh Trail to bolster their operations in South Vietnam. This invasion served to reignite the Laotian Civil War, plunging the country once again into turmoil. The same year marked the U.S.'s decision to become actively involved in the Vietnam War, intertwining the fates of these neighbouring nations.

Operation momentum: The CIA's covert war in Laos

Laos, with its mounting political instability, presented a potential domino that the U.S. was determined to keep upright. President Eisenhower's response in 1961 was to approve the CIA's Operation Momentum. This covert initiative aimed to arm and train the Hmong, one of the largest ethnic minorities in Laos, under the leadership of Vang Pao, to combat the rising communist forces of the Pathet Lao[3].

!["Gen. Vang Pao With Prisoners" By manhai [CC BY 2.0], via Flickr Laotian General with Prisoners, Gen. Vang Pao, right, commander of the Second Military Region in Laos, talks in Sam Thong, Laos on Oct. 17, 1969, with two prisoners captured during fighting with the pro-Communist Pathet Lao near the Plain of Jars. Vang identified these prisoners as North Vietnamese to support the Laotian claim that North Vietnamese forces are in Laos fighting at the side of the Pathet Lao.](/_next/image?url=https%3A%2F%2Fimages.ctfassets.net%2Fa7zy8squzsbw%2F3x2w3k8PIJn2yId87QqGhz%2F217f74899572c2a7162bf8918f574cfb%2Fvang_pao.jpeg&w=1920&q=75)

"Gen. Vang Pao With Prisoners" By manhai [CC BY 2.0], via Flickr

The Hmong, a hill tribe who lived on peaks and high mountain plateaus, had a longstanding reputation for resisting authority. For centuries, they had found themselves in conflict with the lowland Lao majority. The CIA, recognising an opportunity within this historical strife, strategically exploited it to their advantage. The complex interplay of cultural, political, and military elements in Laos was thus woven into the broader tapestry of Cold War geopolitics.

ℹ️ In the aftermath of World War II and throughout the Cold War, the United States was unrelenting in its efforts to cut down the spread of communism across the globe. South-East Asia became a principal focus for the U.S., driven by the threat of the so-called Domino Theory, which predicted that if one country in a region became communist, others would inevitably follow

In 1962, under the directive of President Kennedy, the U.S. initiated an international conference in Geneva on May 16th to discuss the ongoing situation in Laos. The conference convened representatives from all the countries that had been involved in or influenced by Laos' turbulent history. This included Laos, the U.S.S.R., the People's Republic of China, North Vietnam, South Vietnam, Poland, the United States, France, the United Kingdom, India, Burma, Cambodia, Canada, and Thailand. As the international community gathered to deliberate, the three principal Laotian factions managed to reach an agreement on June 12th concerning the composition of a coalition government. The Geneva conference culminated in the Declaration on the Neutrality of Laos on July 23rd [4]. The declaration was a pledge by all signatories to refrain from intervening, either directly or indirectly, in Laos' internal affairs. This encompassed prohibitions against forming military alliances with Laos or establishing military bases on its territory. However, these agreements were fragile and quickly deteriorated. The once-promising path toward peace and neutrality was disrupted, and the presence of American, Thai, and Vietnamese forces in Laotian territory became a significant factor once again.

The year 1964 marked an escalation in American interference in Laos with the initiation of covert bombing missions, known as Operation Barrel Roll and Operation Steel Tiger. The primary objective was to disrupt and hinder the Ho Chi Minh Trail, a network of paths and tracks used by North Vietnam to transport supplies and troops to South Vietnam, crossing through Laos and Cambodia.

The United States used military aircraft such as the AC-130 and B-52, laden with cluster bombs, to carry out these attacks. The missions were secretly stationed in Thailand, and the bombing of Laos was conducted without the consent or approval of the international community. In fact, for many years, the bombing missions were kept secret even from the United States Congress.

The aftermath of the secret war

Between 1964 and 1973, the United States engaged in relentless bombing over Laos, dropping the equivalent of a planeload of bombs every eight minutes, 24 hours a day, for an entire nine-year period. The Laotian Civil War ended in 1975, leaving behind 200,000 civilians and military personnel dead, comprising around 10% of the Lao population at the time. Tragically, it is estimated that an additional 20,000 people have since been killed by unexploded ordnances (UXO).

💡 The callous indifference exhibited by the U.S. towards Laos during these operations is perhaps the most horrifying aspect of this historical episode. Collaborating with Thailand and utilising its bases, American pilots were ordered to discard unused cluster bombs over the jungles of Laos prior to landing in Thailand. This practice, born from the risks associated with landing with these explosives, was carried out under the presumption that the area was mostly uninhabited. It reflects a blatant disregard for the potential enduring impacts on both the Laotian environment and its people.

Laos accounts for more than half of all confirmed cluster munition casualties worldwide, an alarming statistic for a country with a population of only 7.4 million people.

Map of US bombs dropped over Laos between 1964 and 1973

As a nation heavily reliant on agriculture, Laos faces ongoing challenges, especially since it is still a developing nation. Many families outside urban areas depend almost entirely on their own farming and resources from the Mekong river. However, the fear of hidden UXO has left significant portions of arable land unusable, as farmers worry about accidentally detonating a buried bomb. The situation is further exacerbated by children who unknowingly play with UXOs, leading to serious injuries and fatalities.

Such fears have left around 37% of otherwise cultivatable land unused. This situation is especially dire for a nation where poverty is prevalent and the economy is struggling to grow.

In addition to UXO, the residual effects of large quantities of defoliants and herbicides, including Agent Orange, continue to affect the people and environment of Laos. Chemical pollution still contaminates food sources and water bodies, leading to disabilities in newborns.

One of the regions most impacted is the enigmatic Plain of Jars, a megalithic archaeological site in northern Laos. Comprised of over 90 jar sites, the Plain of Jars became a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 2019. However, the threat of UXO has kept all but three sites closed to the public. Efforts to clear the area of UXO are ongoing, but the sheer number of hidden ordnances makes it hard to predict when the site will be entirely safe.

!["Plain of Jars, Phonsavanh, Laos" By David McKelvey [CC BY 2.0], via Flickr Three jars in a line from the Plain of jars. The jars sit on green grass where you can see some trees scattered around. In the background, some hills and the sky, covered by clouds](/_next/image?url=https%3A%2F%2Fimages.ctfassets.net%2Fa7zy8squzsbw%2F11JrBir3v7mh0TP7SyC9RQ%2F41173da62503b2313dd0d4ba8d91b047%2F15026640380_3d68f9a38f_c.jpg&w=1920&q=75)

"Plain of Jars, Phonsavanh, Laos" By David McKelvey [CC BY 2.0], via Flickr

The widespread poverty in Laos has also led some to see the leftover scrap metal from bombs as a valuable trading commodity. The demand for UXO scrap, despite its dangers, has surged along with scrap metal prices. Local markets in Laos often feature vendors selling objects crafted from both exploded and unexploded bombs, reflecting the grim intersection of economic necessity and a painful historical legacy.

COPE and MAG organisations

Unfortunately, the story of the war fought in Laos isn't widely taught in the Western world. Many of us learn little about the Vietnam War, at least in Italy, let alone the Secret War on Laos. We first encountered this hidden chapter of history during our stay in Vientiane, where we had the opportunity to visit the Cooperative Orthotic and Prosthetic Enterprise (COPE) museum. Nestled in the heart of the Laotian capital, this small yet meticulously curated museum showcases COPE's mission: providing affordable, quality rehabilitation services to those affected by UXO.

The entrance to the museum is free, but donations are encouraged to support the cause. Inside, you'll find stories of young children who have lost an eye, arm, or leg, their faces scarred, only because they played in a dangerous area littered with hidden bombs (or bombies as the locals define them).

COPE works to provide a mobile service reaching the most remote areas in Laos - these medical teams offer support and prosthetics to people who would otherwise find it difficult to reach fully equipped hospitals.

Prostheses on display at the COPE museum in Vientiane

During a subsequent visit to Luang Prabang, we explored another branch of the COPE museum where we were introduced to the Mines Advisory Group (MAG). This organisation's primary mission in Laos is to rid the country of UXO. In addition to their clearance efforts, MAG also educates the local population about the dangers of UXO. Their efforts include teaching people, especially children, how to recognise UXO and what actions to take if one is discovered. A team of experts and volunteers actively search for and detonate UXO. You can discover more about their process here, but in essence, it involves:

- Identifying endangered areas, often through word-of-mouth from villagers where injuries have occurred

- Sending a team of experts, utilising trained sniffing dogs and specialised equipment, to locate the bombs without causing detonation

- Mapping the locations of ordnance for easy retrieval by demolition experts

- Calling in a team of artificers to safely detonate the bombs

Once an area is cleared, it's returned to the villagers for safe use. Unfortunately, the process is time-consuming and labor-intensive. The team at MAG manages to clear around 20,000 bombs each year.

In 2016, President Obama, the first U.S. president to ever visit Laos, announced that the U.S. would donate $90 million to help clear the country of UXO.

Even with this support, and the continued efforts of organisations like MAG, the task remains monumental. Estimates suggest that it could take anywhere between 100 and 200 years to completely rid Laos of all UXO, with some projections even reaching nearly 1000 years. This stark figure underscores the enormity of the problem and the enduring legacy of a war that may be out of sight but continues to impact lives every day.

The (partially) unfulfilled promise and the convention on cluster munitions

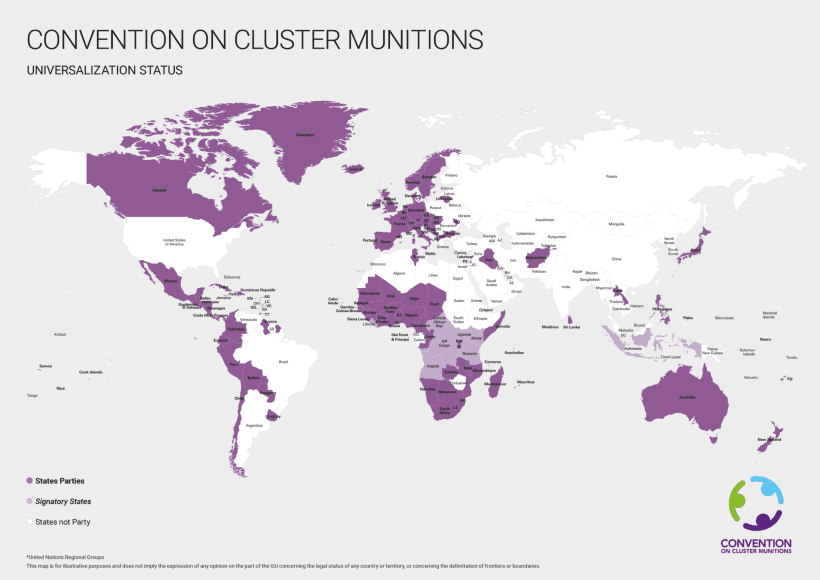

On May 30th, 2008, the Convention on Cluster Munitions was adopted in Dublin and opened for signature in Oslo on December 3rd of the same year. The Convention prohibits all use, production, transfer, and stockpiling of cluster munitions in any future conflict around the world. This was enacted in recognition of the lingering harm these weapons cause; their impact extends far beyond the duration of the war, affecting generations who had no part in the conflicts.

As of July 2023, a total of 124 states have committed to the goals of the Convention. Unfortunately, key nations such as the USA, China, Russia, and Israel have not signed the agreement. This absence suggests that cluster munitions could again be deployed in future battles, potentially creating more situations akin to the tragedy in Laos. Indeed, recent reports reveal that Ukraine has started launching the first cluster bombs in its war against Russia, with bombs provided by the US. The lingering effects of these bombs will continue to torment the territories where they fall, affecting innocent individuals for many years to come.

Map of signatories of the Convention on Cluster Munitions as of march 2023. / Credits: https://clusterconvention.org

I hope this article has ignited a spark of interest in you about this critical issue. If you would like to delve further into the Secret War on Laos, I highly recommend watching this video (unfortunately, it is only available in Italian):