Malaysia is a blend of various cultures, made up of a multitude of ethnicities that contribute to an extensive array of linguistic, cultural, and religious traditions. Within this complex demographic landscape, a noteworthy division exists between indigenous communities, known collectively as bumiputra, and immigrant groups, chiefly those of Chinese and Indian heritage, termed non-bumiputra.

The bumiputra group, including Malay, Orang Asli, and other smaller tribal communities, makes up about 62.5% of the country's population. Chinese residents constitute around 21%, and Indians about 6.5%, while the remaining 10% are non-citizens from diverse backgrounds, including some from Europe.

Naturally, Malaysia's current diversity wasn't always the norm. Up until the early 19th century, the country was largely demographically consistent, mainly populated by Malays who made up around 90% of the residents in Peninsular Malaysia as of 1880. The landscape began to shift when the British took control in 1874 and governed until Malaysia's independence, in 1957. Their governance instigated a notable change in the country's ethnic makeup. Encouraging migration from other parts of their empire, particularly China and India, the British administration effectively altered Malaysia from a predominantly Malay society to a more pluralistic, multi-ethnic community[1].

Undoubtedly, Malaysia's rich cultural amalgamation has significantly influenced its history, architecture, customs, and even its cuisine. Malaysians dishes—which happen to be our favourite in Southeast Asia—are incredibly diverse and flavourful. You'll notice that many Malaysians meals incorporate elements from various culinary traditions, creating unique and delectable dishes. As much as I'd love to talk about the joys of Malaysians cuisine, that's a topic for another day.

Having so many different ethnicities living all together, also come with its own challenges, something that Malaysia has been trying to address since it independence in 1957. Visiting Malaysia you often hear and read about unity, but total and real unity does not come easy and needs to be fought for. That is way even after the British finally left the country, Malaysia has continued to face an array of issues that have had a lasting impact on its political climate. These challenges aren't just relics of the past; they are pertinent topics that will likely continue to shape the country's political landscape for years to come.

Ethnicities of Malaysia

Before diving deeper into the multifaceted issues connected to ethnicity and culture, it's crucial to outline the origins and dynamics of Malaysia's diverse ethnic landscape.

People walking in mlaysian street / Credits: DALL E

Malay

The Malays trace their origins to the Malayo-Polynesian linguistic group, indicating ancestral connections to the mariners of Borneo who migrated to the Malay Peninsula roughly 1,500 years ago.

Making up 50.1% of Malaysia's populace, the Malays serve as the country's most prominent ethnic community, wielding considerable influence over its economics, culture, and politics. Malay is the national language, and Islam, practiced by the majority of Malays, is the country's official religion. Historically, Malays were known as a coastal trading society with adaptable cultural traits. Today, a large portion of the Malay community resides in rural villages as opposed to urban areas.

Malay culture is an amalgamation of various influences, having absorbed, adapted, and even disseminated elements from other local ethnic groups, including some aspects of Javanese culture. Over the centuries, Malay culture was shaped significantly by Hinduism, Buddhism, and animism. The widespread adoption of Islam among Malays only occurred in the 15th century, prior to which the community was predominantly Hindu.

Chinese

In contrast to the Malays, the second largest ethnic group in Malaysia, Chinese Malaysians, are not originally from the peninsula. Making up 21% of the country's population, Chinese Malaysians have been part of the nation's fabric for many centuries. However, their numbers swelled substantially during the 19th century under British colonial rule. It's crucial to note that the term "Chinese" isn't monolithic; Malaysia is home to various Chinese subgroups, including Cantonese speakers mainly found in the capital Kuala Lumpur, as well as Mandarin and Hokkien speakers. While Taoism and Buddhism are the predominant religions among this group, there's also a Muslim subset.

Over time, the Chinese community has woven aspects of Malaysian culture into their own, often through intermarriage with indigenous and other ethnic groups. This has given rise to a blended culture that reflects broad range of traditions. Initially, Chinese immigrants were predominantly involved in railway construction and tin mining. However, they eventually transitioned into owning businesses, and today they play a significant role in the country's business and trade sectors.

Indian

The Indian community ranks as the third largest ethnic group in Malaysia, comprising approximately 6.7% of the total population. Their migration to Malaysia became notably significant during the late 19th and early 20th centuries, a period when the British Empire was at its zenith. Given that Malaysia was under British rule, many Indians ventured here seeking improved economic prospects. Today's Indian Malaysians are predominantly of Tamil descent, though other subgroups like Telugus and Punjabis are also present. Initially arriving as labourers to work on railway construction, plantations, and in rubber and oil palm industries, they have now ascended into various professional roles in modern Malaysia.

In terms of religion, Hinduism is the predominant faith among Indian Malaysians, although Christianity and Islam also have a following within the community. Indian influence extends beyond the professional sector and is particularly noticeable in Malaysian cuisine. Many classic Indian dishes have been embraced and adapted locally, further enriching Malaysia's culinary landscape.

Orang Asli

The remaining portion of Malaysia's diverse population primarily consists of the Orang Asli, which translates to Original People. Often thought of as one large group by people unfamiliar with the region, the Orang Asli are actually made up of many different tribes and communities. Each has its own language, cultural practices, and traditional lands. Despite these differences, all Orang Asli tribes share a common heritage as the descendants of the earliest known settlers of the Malay Peninsula. Some researchers even posit that the initial tribes may have arrived as far back as 25,000 years ago[2].

Traditionally, the Orang Asli believed in animism, thinking that spirits lived in natural objects like trees and stones. However, in recent times, some have adopted major religions like Islam and Christianity.

For work, most Orang Asli are involved in agriculture, especially rice farming. Those living near the coast often rely on fishing. As cities have grown, a good number have moved to urban areas, taking on a range of jobs. Despite their presence, they're not strongly represented in the country's politics, having only one seat in the national parliament.

Underneath the surface of the ethnic divisions in Malaysia

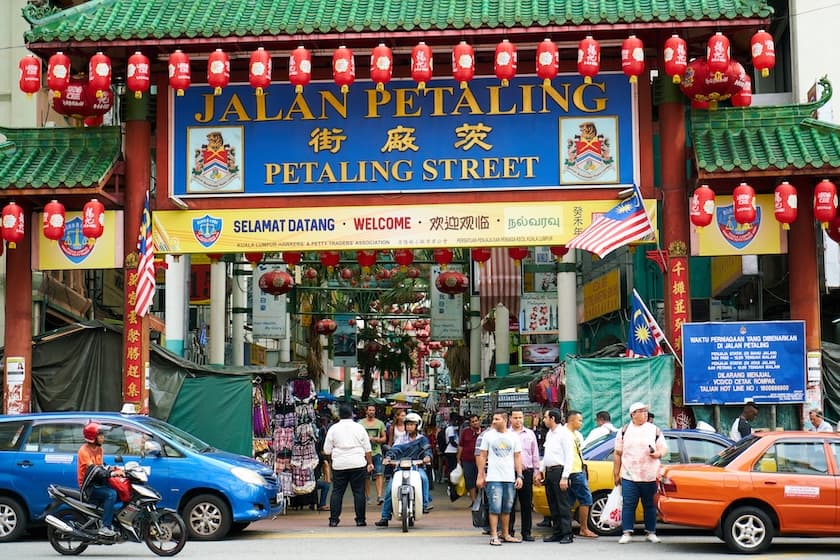

At first glance, Malaysia's diverse ethnic communities seem to coexist harmoniously. However, during our travels, we discovered that the reality is a bit more complex. We noticed that cities often have distinct neighbourhoods primarily inhabited by specific ethnic groups. For instance, in Georgetown's Little India, you'll mainly find people of Indian descent, while in Kuala Lumpur's Chinatown, the Chinese community predominates. While some areas do display a mix of ethnicities, it's more common to see people socialising mainly within their own communities.

Entrance of Chinatown, Kuala Lumpur / Image by freestockcenter on Freepik

As a tourist, you're unlikely to experience palpable tensions between ethnic groups. But if you dig a bit deeper, you'll notice that these divisions exist. Conversations with locals and online research revealed that the current political climate might be exacerbating these divisions rather than healing them.

Malaysia operates as a federal constitutional monarchy, made up of thirteen states and three federal territories. It stands as one of the few multi-party democracies in Southeast Asia. Since gaining independence in 1957, Malaysian politics has had ethnicity at its core. Political parties often tailor their election campaigns to win the support of specific ethnic groups. Even voters, while considering economics and governance important, tend to gravitate towards parties that align with their ethnic backgrounds[3]. This ethnic focus in politics is so prevalent that it's even reflected in a popular game called Politiko, where players aim to win voters for their represented political party.

Factors like religion and the current educational system are key players in sustaining these divides. Both, often serve as powerful tools in deepening the gaps between different communities, rather than building bridges.

The religious landscape of Malaysia: Secular or not?

Malaysia's rich cultural diversity naturally extends to its religious practices. According to the 2020 Population and Housing Census, 63.5% of Malaysians identify as Muslim, 18.7% as Buddhist, 9.1% as Christian, and 6.1% as Hindu. Other religions—like animism, Confucianism, Taoism, Sikhism, and Jehovah's Witnesses—make up the rest of the spiritual mosaic. This diversity isn't just in the numbers; it's visually evident, too. While roaming through cities, it's common to spot a mosque, a church, and temple within close proximity to each other.

🔎 Notably, openly identifying as an atheist isn't common due to potential government discrimination, a point often highlighted by human rights advocates.

Although Malaysia was initially established as a secular state, its constitution complicates this designation by stating, on Article 3, "Islam is the religion of the Federation; but other religions may be practiced in peace and harmony." Furthermore, Article 160 stipulates that "to be considered Malay, one must be Muslim". Both federal and state governments hold the authority to regulate religious doctrine for Muslims and primarily promote Sunni Islam, leaving other Islamic sects in a precarious, often illegal, position.

Impressionist painting of a mosque, and hindu temple and a buddhist stupa located close to each other. / Credits: DALL E

Malaysia operates under a dual legal framework, which involves both civil and Sharia (Syariah) law systems. Each of Malaysia's states is responsible for its own Sharia legislation. A notable recent development came in November 2021, when the Sultan of Kelantan, Muhammad V, approved the Kelantan Syariah Criminal Code Enactment 2019. This enactment outlines 24 new rules that are now mandatory for all Muslims in the state of Kelantan. Among these are the criminalisation of apostasy, the distortion of Islamic teachings, and not respecting the holy month of Ramadan[4]. Violators can face penalties ranging from fines to imprisonment of up to three years and even corporal punishment.

The enactment has raised considerable concern, especially among advocacy groups like Sisters in Islam (SIS), Legal Dignity, and Justice for Sisters (JFS). According to a report they published in March 2022, the new code perpetuates discrimination and fuels stigmatisation against already marginalised communities. The report emphasises that the legislation disproportionately impacts women, particularly those who are single or entrepreneurs in the beauty and cosmetics sector. Furthermore, it adversely affects human rights defenders, sex workers, and women who identify as lesbian, bisexual, queer, or transgender.

Muslims who seek to convert to another religion, or to give up religion completely, face a complex and arduous journey, involving the need for approval from a Sharia court to officially become "apostates." These courts are generally reluctant to grant such permissions, particularly for ethnic Malays and those born into Islam[5]. For those who had once converted to Islam, leaving the faith is even more challenging. On the other hand, the law does not restrict the rights of non-Muslims to change their religious beliefs and affiliation, and in fact conversion from other religions to Islam is not only welcomed, but highly favoured by the government. While travelling in Bangkok, we encountered a young Malaysian of Chinese descent who chose to leave Malaysia, citing the government's favouritism toward conversions to Islam as his main reason. He shared that officials had repeatedly approached his father, offering a lump sum of money trying to persuade him to convert to Islam. Further, he mentioned that the government even provides tax benefits to incentivise people to make the religious switch. Despite the financial allure, his Buddhist father chose to maintain his faith. Yet, it is not difficult to imagine that many others will opt for the benefits and convert.

This increasing focus on "Islamisation" in Malaysian politics has garnered attention and concern from human rights organisations and religious leaders, including those within the Islamic community. They express alarm over the use of sophisticated social media campaigns by conservative Islamic groups, aiming to sway the younger generation toward a more traditionalist interpretation of Islam.

The duality of vernacular schools in Malaysia: A double-edged sword

While in Ipoh, we caught up with a local Grab driver who shed light on the often-debated topic of vernacular schools in Malaysia. Curious to dig deeper, we plunged into a sea of online articles and found that this is indeed a complex and ongoing issue.

The concept of vernacular schools in Malaysia has its roots in the 18th century when Chinese and Indian immigrants viewed themselves as distinct from the native Malay population. To preserve their unique identities, they opted to set up their own separate educational institutions. This trend was perpetuated during the 19th-century British colonial rule, which also introduced English-medium missionary schools. The British saw value in maintaining these vernacular schools as they helped in preserving cultural identity and continuity.

Even after Malaysia achieved independence in 1957, these schools have persisted. While no law explicitly prevents children from one ethnic background from attending a school that teaches in the language of another, in practice, parents generally prefer to send their kids to schools that align with their own ethnic and linguistic heritage. This is particularly evident in Chinese and Tamil schools, which predominantly cater to students from their respective ethnic communities. Malay schools, on the other hand, often see a more diverse enrolment, including Chinese and Indian students.

The underlying idea for the existence of vernacular schools is commendable. These schools aim to preserve the language and cultural heritage of minority ethnic groups, ensuring these traditions are passed down to the next generation. However, there's also a flip side to this. The separation of children based on ethnicity and language from a young age can inadvertently build social barriers. These divisions make it more challenging for young people from different ethnic backgrounds to interact and understand each other, which can perpetuate divisions later in life.

Most vernacular schools in Malaysia are at the primary level, and by the time students reach secondary school, they're typically integrated with peers from various ethnic backgrounds. However, this still means kids spend about six formative years in ethnically homogeneous environments. When coupled with any pre-existing prejudices they may pick up from their families, this setting can cultivate bias against other ethnic groups—a difficult mindset to change even as they grow older. Despite the education system's focus on promoting unity amid ethnic diversity, a telling survey revealed that at least 80% of participants still harboured some form of prejudice against other ethnics groups[6]. While relations among different ethnic groups may seem harmonious on the surface, the underlying reality is less rosy. Students often find it hard to engage in simple social activities with those from other backgrounds—be it cohabiting as roommates or housemates, participating in group learning, or even sharing a meal

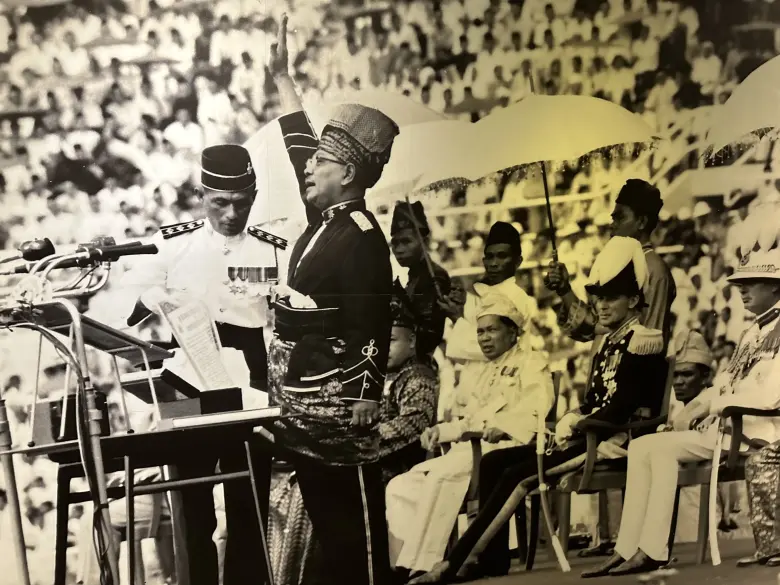

Tunku Abdul Rahman proclaiming "Merdeka", on 31 August 1957

In an attempt to mitigate ethnic divides, an Ethnic Relations Module was introduced as a mandatory course in all public universities back in 2005. The course underwent revisions in 2012 following some criticism, but even the updated version has sparked some controversy[7]. According to critics, some academics have used the course as a platform for indoctrination rather than education. Prominent human rights lawyer and activist Siti Kasim frequently highlights issues such as this. A liberal Malay Muslim herself, Siti is highly critical of current government policies and often speaks out about the need to leave religion out of the schooling system. She's even gone as far as to label Malaysia's national schools as "indoctrination factories for Malay children”, voicing concern that the school system is creating a society that is increasingly polarised, by dividing the country along ethnic lines.

Conclusion

It's not my place to pass judgment on how a country navigates its cultural complexities, minority relations, or education system. I'm merely a traveler, and certainly not an expert in these areas. The aim of this article is to shed light on issues that I find significant, partly because they echo challenges we also face in my homeland, Italy, albeit in different ways.

Spending a month in Malaysia gave me a snapshot of the country's cultural landscape. While the divisions aren't immediately obvious to a visitor, deeper investigation reveals a different picture. Malaysia is undoubtedly a stunning country where I've felt warmly welcomed by individuals from all ethnic backgrounds. However, as outlined in this article, ethnic divisions do exist, and like any societal challenge, they're best addressed sooner rather than later to prevent escalating tensions.

Malaysia has made remarkable strides since gaining independence in 1957 and I'm confident that the nation can work through the issues highlighted here to attain the complete national unity that so many Malaysians value. Achieving this will require collective effort, dedication, and unity from all Malaysians. My hope is that they'll pave the way, setting an example that inspires other countries to follow suit.

References

- Historical Overview of Malaysia's Experience in Enhancing Equity and Quality of Education: Focusing on Managem - Hazri Jamil

- Orang Asli - encyclopedia.com

- Malaysia’s 15th General Election: Ethnicity Remains the Key Factor in Voter Preferences - Fulcrum

- How Kelantan’s latest Shariah criminal code law affects the marginalised and minorities - Malay Mail

- 2022 Report on International Religious Freedom: Malaysia - US Department of State

- Racial Integration of Multi-Ethnic Students in Malaysia Higher Institutions - International Journal of Academic Research in Business & Social Sciences

- Ethnic relations module used by some for indoctrination - Malaysia Kini